(text first published in Whanganui River Annual 2001)

I can never forget 1947. Leaving my hometown of Dunedin and heading for my

first country school, I was bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, as they say, full

of the crusading eagerness of youth.

As Ethne Davidson had discovered before me, it was certainly "in the country".

Unlike Ethne, I stepped down from the Limited at Raurimu with no-one to

meet me, and spent the night sitting on a little cane-backed chair in the station,

only to be awakened every time a train came through a neighbouring station by

the dead-awakening clanging of the tablet machine alarm. I can still see the

top snowclad face of Ruapehu shining in the moonlight for hour after hour.

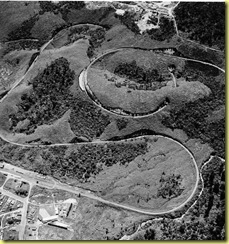

Raurimu Spiral :Photo taken 24/1/57 by Whites Aviation.

(Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library necessary before re-use of this image.)

Like one of the Annual's earlier contributors, I knew that it was a mere

40k to Whakahoro, but the mailtruck had covered almost 200k up every side

road, to every mailbox, to every cream stand, by the time Mousie Shaw pointed

across the

Retaruke and said, "There's where you'll be staying!" It had been

a 5-hour trip! And as he eased the truck up the gentle slope toward the

farm gate, I saw the Hayes family, all except Mum, waiting to meet "the new

teacher". Old Fred himself, complete with a long piece of grass hanging from

his mouth, a week or more of black stubble all over his tough and experienced

face, was perched on the gate itself, with the kids on the grass in front of

him. "We're a bit rough and ready," he barked, "but just take us as you find

us!"

The kids loaded my trunk onto a home-made barrow, and were clearly eager to

show me the bridge, the like of which I had never imagined, let alone

encountered. It was a swingbridge about 30 metres above the water, and more

than 30 metres long. The huge rectangular uprights looked pretty solid and

permanent, and at first glance the "cables" appeared to be about 50mm thick,

and well able to take the load. Closer examination showed that each cable was

in fact a bunch of No. 8 or No. 10 wires held together at intervals. Freddy

used to joke about it, saying that you'd have plenty of time to get off the

bridge if they went, as you'd hear each wire snapping in turn "ping - ping -

ping -...", and the kids would shriek with laughter and take up the tale.

But the worst aspect of the old bridge at that time was the neglected

decking. Fred had renewed a few vital planks, but while I was there about a

third of the planks were lying in place without being nailed down, so that

you dare not stand on one end of a plank. Another third were properly fixed,

and the remaining third missing altogether. The views one got through some of

these gaping holes of the wet papa boulders below were enough to send a new

chum into a quivering mess. The Hayes family delighted in telling me that

Bill Lacy, well over six feet and with the typical Lacy assertiveness,

actually crawled the last metres of his first crossing. I wasn't much better,

as the kids galloped ahead of me with the laden barrow, causing the bridge to

buck and weave, and the city lad wondering why he had ever volunteered for

country service!

Mrs Hayes welcomed me like a son and a guest, and I was the only one who

slept with sheets. The boys slept on the verandah, sheltered by some

makeshift sacking nailed between the verandah posts, and for extra bedding, a

cow cover or two, and they were quite happy with that. After I'd been

boarding there a few weeks I could cycle down the drive, down the twisty

track, onto the bridge, then stay three planks from the right to halfway,

cross the bridge, then stay three from the left to complete the crossing. I

couldn't always stay on the bike up the muddy track to the road, but the

bridge was no longer a worry. Years later, of course, the old bridge

collapsed while two of the Hayes boys were taking a mob of sheep across, and

it was actually the tall timber supports that failed in the finish, rather

than the wire cables.

The little prefab school was still quite new when I took over. The nine

children, four Hayes, two Lacys, two Wilsons and one little Dobbs, lined up

outside to say "Good Morning", and I heard for the first time the refrain

that was to be repeated for more than a month, "This is how Miss Dron did

it."

Whakahoro School 1947:

Don Wilson, Bob Hayes, Jill Hayes, Bunny Lacy, Rodney Hayes, Isla Hayes, Clare Wilson, Claire Lacy, Jenny Dobbs

We had a rough rugby post out on the paddock which ended at the

Whanganui River bank, and Bob Hayes would kick goals with his bare feet.

The Hayes kids would walk, or ride the pony, three miles to school, while

the others lived quite handy. The Lacys lived across the Retaruke, and had

to walk up to the traffic bridge that figures in your 2000 issue. It was on that

little piece of road that I saw some wonderful glow-worm displays as I walked

home to Lacys when I boarded there. Bob and Jill Hayes, in particular, taught

me volumes about nature, knowing all the native trees, and Bob could even

show me the glow-worms during the day!

Every weekend I would be invited to go "pig-untin", and I held out for a

while on the grounds of not being very keen to kill things anyway. I was a

teetotaller too, fresh from my Methodist adolescence, and again the Hayes

kids roared aloud so honestly when I first said "Don't touch the stuff

actually." Fred Hayes' reply, "You will before you leave this place!", turned

out to be prophetic. I gave in on the pig-hunting too, and this was another

eye-opener for the green youth from town. When Spot or Blue would scent a

pig, and be off through the bracken and the bush, we'd all stand and listen,

waiting for the barking which signalled a bail-up. Then off we'd go, three or

four men and as many kids, straight up through the bush, gradient or no

gradient, just heading towards the sound. I ran quite well in Wanganui that

year across country, and I'm sure the pig-hunting had something to do with

it.

I also trained after school on the road and over the farmland, one of the

best courses being up the winding track behind the Hayes woolshed, and

across the rugged and undulating top country which joined the Hayes place

to that of the Lacys on the north bank of the Retaruke. I was running across

this uneven land one afternoon when I heard someone yelling and cursing on

the hill opposite. It was Bill Lacy, who had come in from Owhango to work on

some of his stock at Whakahoro. The language was so florid, unprintable and

entertaining that I sat on a rock overlooking the valley, and watched the

drama. It was ".. crazy bloody bitch!" and "... wait till I get you, you

stupid, bloody mongrel!" and "... half-witted piebald bastard!" until

eventually the dog managed to get the whole mob moving quite nicely down

the hillside by barking above them. Just when Bill had run out of swearwords,

and had succeeded in getting the dog to obey him, the dog in question got it

into his head to run straight down the hill, splitting the flock in two, and

sending the demented sheep in all directions. Bill Lacy threw down his hat,and

roared to the world in general, "You Protestant cur!!" I could hardly run for

laughing.

While I boarded with the Hayes family, I was aghast at the workload that

fell to the lot of Mrs Hayes and her children. Their father had told his kids

that if they milked the cows, they'd get the cream cheque at the end of the

year. Whether they ever saw the money is anyone's guess. There were 24 cows

while I was there, and four kids, ranging from Blondie (Isla) at 6 to Bob who

was about 12. Blondie's tender years cut no ice with the others, who knew

only too well that 24 divided by 4 equalled 6, and there she was, out there

in the Autumn cold, barefoot in a muddy yard, no cow-shed, no legropes,

stalking her six cows around the punga-fenced enclosure, and taking twice as

long as the others to do so, morning and night. In school, by 11 am,

Blondie's head would drop and I'd often let her sleep. Maybe she was the

reason I learned how to milk, and for a while she could sleep in in the

morning and stay awake long enough to learn how to read. Isla was to become

a prize-winning horse rider over jumps, before the onset of multiple sclerosis,

of which she died while still a young woman.

I was never much of a swimmer, but Jumbo (Donald) Hayes and I crossed the

Whanganui one morning as part of a shearing team to muster and shear a

small number of sheep just opposite Wade's Landing. They took a rowing boat

over, and a hand-operated horse clipper converted to take a handpiece. I spent

the whole morning winding the handle of this contraption, and I can't even

remember whose sheep they were or who did the shearing. But we returned

by boat, with a couple of half-filled woolbales, and I was most relieved that

Jumbo hadn't challenged me to the return swim.

I had a lot of time for Jumbo. He was about 16 at the time, and returned

home to help on the farm during that year. We shared a bedroom, and Jumbo

wouldn't hear of my offering him one of my sheets to make his life a bit more

comfortable. "I'd bloody well freeze with a sheet around me face!" was his

explanation. He was an intelligent and powerful young man, who understood

and perceived more clearly than his younger brothers and sisters the stress

and strain that was being put on their mother in particular. I had experienced

tension in the home as a child myself, but I was not prepared for the worn-out

spectacle of a household drudge that Mrs Hayes had become. She was an

accomplished pianist, and had concert experience, but the constant battle

against hostile conditions and inadequate resources was wearing her down. In

the short time I was there I grew to like and respect her, for where would

they have been without her? Jumbo was in fact a kind of silent threat to his

father, and he was big enough and brave enough to challenge his Dad if ever

he went too far in his treatment of people or animals.

My efforts to get to Wanganui from time to time to run with the harriers

and compete in particular races left some interesting memories. The

Dempseys, who lived about three miles up the Retaruke, had rung to offer

me a lift to Raurimu if I could get to their place. So Frank Lacy saddled up

a horse for me, and I rode to Dempseys after school on a Friday. The real

drama was enacted on the return journey, when I decided to hitch-hike on the

Sunday from Raurimu to Dempseys wearing an overcoat and carrying a little

leather suitcase, not the ideal gear for a long walk! I'm now not sure how

long it took, but I passed through Kaitieke, the Owhango turnoff, the

Kawautahi turnoff, the Upper Retaruke turnoff, and Dobbs's Bluff without

seeing a single car. Even the stamina born of hundreds of miles of running

was wearing extremely thin when I staggered onto Mrs Dempsey's verandah

after my 40-kilometre trudge. "Oh, you poor boy!" said she, and her tea and

cakes were a godsend.

However, my troubles were not entirely over! For out there in a 20-acre

paddock, stood my horse, and when I approached him to saddle up, he lifted

his head, swivelled around, and trotted away to the far corner of the soft,

uneven field, giving me no option but to walk again. At least he stood still

this time, and I walked him onto the road for the 5k ride home to Lacys'.

Like Isla Hayes in school, I simply couldn't stay awake, and fortunately this

quiet, homeward-bound steed carried me home undirected.

When I speak of Whakahoro, my wife reminds me that I'm living in the past;

yet she enjoys her own reminiscences likewise. But that unique valley does

hold a special place in my memory, for some of the reasons suggested above.

So what a thrill it was in recent times to find on the Internet, a 4-picture

spread of the Hayes house and the infamous Berryman Bridge, which had replaced the old one in the 80s.