More Te Rata History

The Te Rata farm is situated on the north bank of the Retaruke

River about 5k from its confluence with the Whanganui. The

house, built on a small flat paddock above a narrow gorge of the

Retaruke, was originally known as the Wade Homestead, Mrs Wade

being a Lacy from further downriver. The only reasonable access

to the house from the Raurimu-Whakahoro Rd was by way of a

traffic-width swingbridge, with massive uprights and "cables" made

from the good kiwi expedient of wrapping together clusters of

No.10 fencing wire. From any distance they appeared to be

genuine cables about 40-50 mm in diameter. The bridge was said

to be about a hundred feet above the water. When I first

encountered this fearsome bridge in the 40s, vehicles had long

since been unable to use it, owing to the very questionable state

of repair of the decking timbers in particular, but also because

of justified anxiety about the bridge's load-bearing capacity.

As a young greenhorn teacher, I was about to board at the Te Rata

homestead with the Hayes family, four of whom I would actually

teach. My first terrified crossing of the bridge was preceded by

this pack of lively mischievous kids running across with my bags

in an old farm wheelbarrow, and taking great delight in making the

bridge whip and shake as I carefully picked out the parts of the

decking which were safe to step on. About a third of the planks

were missing altogether at that stage, and another third

completely unnailed, and I still find it incredible that I

actually learned to cycle across within a couple of weeks of trial

and heart-stopping error. This infamous bridge I will refer to

hence as the Hayes Bridge, as distinct from the Berryman Bridge of

recent history, which I understand replaced the awesome Hayes on the same site.

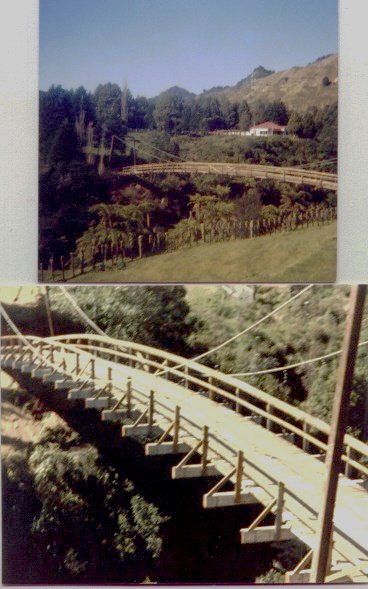

The Hayes Bridge from upstream

The district, part of the Lower Retaruke, was called Whakahoro,

which I think means "canoe launching place", and more specifically

describes the settlement at the confluence with the Whanganui,

where the Lacy family settled and lived for many years. The

school was down there and called Whakahoro also, as was Wade's

Landing, on the Whanganui below the Retaruke. The local Post

Office was at the Dobbs farm-house just upstream from Te Rata, and

was called Retaruke.

I visited Te Rata twice in later years, in the 60s and then the

70s, and by that time, the Hayes bridge had had its decking

completely renewed, but it was still closed to vehicular traffic.

Mr & Mrs Hayes told most graphically the story of an insurance

agent who hadn't been told that, and they were astonished as they

returned from the back paddocks to see a CAR, the first one in 50

years (?), making its way along the grass drive toward the house.

When they approached the driver, whose face was of parchment

hue, he spat out, "Boy, what a bloody bridge! I'm certainly not

going back that way!" The reply he got was, "Well, yes, you are!"

Fred Hayes, who was a rough diamond but a great raconteur, had

always said that the first thing to go on that bridge would be the

cables, but it wouldn't be a problem if you were on the bridge

when it happened, as you'd hear the ping .. ping.. ping as the

No. 10 wires snapped in turn. You'd have plenty of time to get

off! But in fact, the cables were not the first thing to break.

The Te Rata woolshed was on the south side of the river, on the

same side as the road, and so the Hayes Bridge was regularly used

for the movement of sheep to and from the woolshed. I saw two

lambs fall through the faulty decking in 1947, and later watched

them being reared back to health by the Hayes family, by means of

splints on the lambs' legs. But late in the 70s, two of the Hayes

boys, one on each side of the river, watched the old bridge

collapse, as they were trying to control a mob of lambs on the

bridge, when things had gone wrong with the dogs. What actually

went first was one of the huge wooden uprights which carried the

cables and the whole weight of the bridge and its load. When

the Berrymans took over from the Hayes, there was no bridge access

to the house, and the cross-country route over Te Rata farm and

the Lacy country must have been tractor material for any kind of load.

Long before the ill-fated collapse of the Berryman Bridge, I had

recorded a radio documentary broadcast in the Spectrum series on

Radio NZ, in which I referred to the terrible plight of Mrs Hayes,

who had been left without a water tap in the house, after her only

water supply, a corrugated iron roofwater tank, had been taken

away and rolled across the rickety bridge to be set up at the

woolshed for the sheep to be dipped. For the rest of that year,

the tank never came back, and Fred, kind man that he was (?), had

boxed a freshwater spring in the bush to the east of the house, so

that his long-suffering wife could carry water all day long in a

small cream can. When Margaret Berryman heard that programme,

the house water supply was still most unsatisfactory, and they

didn't know about the spring. So off they went into the bush and

found it, and they set up the best house water supply that the

farm had ever had. Margaret Berryman wrote me a letter of

thanks at that point, and in it mentioned the bridge that had been

built by the Army's Fijian trainees out of materials paid for by

the Berrymans.

For the rest of the Berryman story, readers are referred to the

Berryman-saga link, where the whole sorry business is described

in detail, from the death of Kenneth Richards, beekeeper, whose

laden truck crashed through the bridge, through the wrongful

prosecution of the Berrymans for having an unsafe workplace to the

several appeals and reviews and coroner's inquests, which left the

Berrymans penniless, ill and devastated. A second inquest may

still be called, though the Berrymans have not been found utterly

blameless for the eventual collapse of the bridge. The Army,

however, is now seen as responsible as well, for matters of design

and construction, matters that have only recently been revealed by

the release of the Butcher Report on the Internet.